Gravitational waves from black hole smash confirm Hawking theory

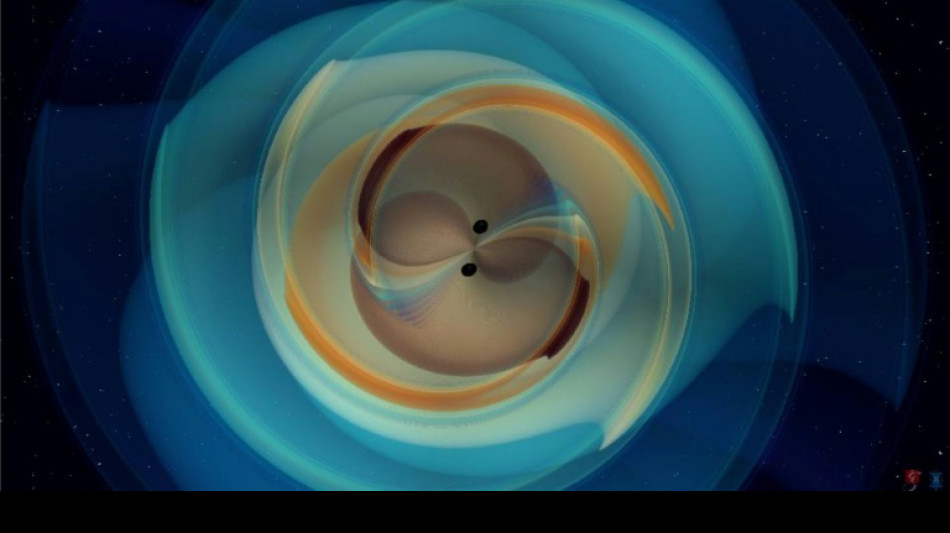

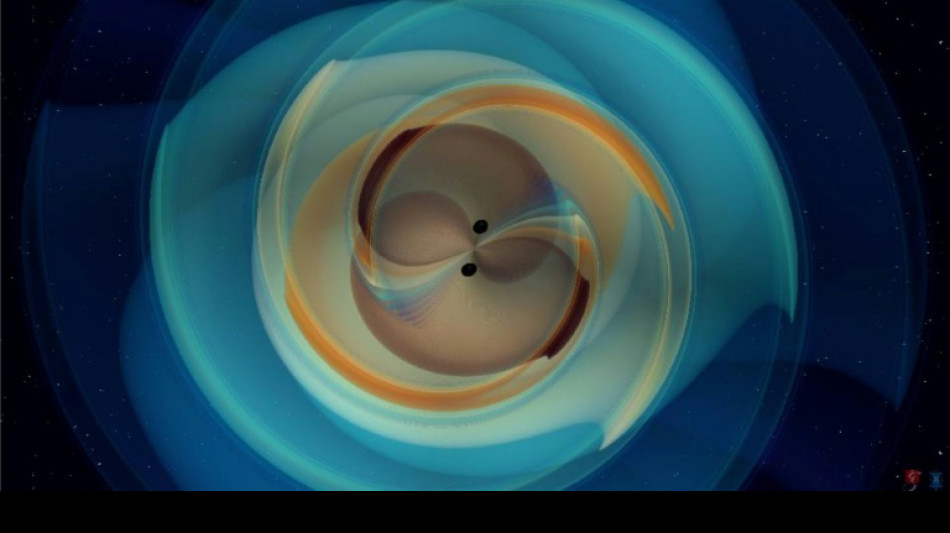

Ripples in spacetime sent hurtling through the universe when two black holes smash into each other -- a phenomenon predicted by Albert Einstein -- have confirmed a theory proposed by fellow physicist Stephen Hawking over 50 years ago, scientists announced Wednesday.

These ripples, which are called gravitational waves, were detected for the first time in 2015 by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-Wave Observatory (LIGO) in the United States.

In his 1916 theory of general relativity, Einstein predicted that the cataclysmic merger of two black holes would produce gravitational waves that would ripple across the universe and eventually arrive at Earth.

On January 14 this year, LIGO detected another of these signals from the distant universe.

That is no longer such a surprise.

Scientists in the LVK collaboration -- a vast network of scientists whose facilities includes gravitational wave detectors in Italy and Japan -- now record a new black hole merger roughly once every three days.

However January was "the loudest gravitational wave event we have detected to date," LIGO member Geraint Pratten of the University of Birmingham, England, said in a statement.

- From a whisper to a shout -

"It was like a whisper becoming a shout," added the co-author of a new study in the Physical Review Letters.

The latest event bore striking similarities to the first one detected a decade ago.

Both involved collisions of black holes with masses of between 30-40 times that of our Sun. And both smash-ups occurred around 1.3 billion light years away.

But thanks to technological improvements over the years, scientists are now able to greatly reduce the background noise, giving them far clearer data.

This allowed the researchers to confirm a theory by another great physicist.

In 1971, Stephen Hawking predicted that a black hole's event horizon -- the area from which nothing including light can escape -- cannot shrink.

This means that when two black holes merge, the new monster they create must have the same or larger surface area than the pair started out with.

Scientists analysing January's merger, called GW250114, were able to show that Hawking was right.

- Ringing like a struck bell -

The black holes collectively started out at 240,000 square kilometres wide, which is roughly the size of the United Kingdom.

But after the collision, the resulting mega-black hole took up 400,000 square kilometres -- about the size of Sweden.

The California Institute of Technology said that working out the final merged surface area was "the trickiest part of this type of analysis".

"The surface areas of pre-merger black holes can be more readily gleaned as the pair spiral together, roiling space-time and producing gravitational waves," it said in a statement.

But the signal gets muddier once the black holes start combining into a single new monster.

This period is called the "ringdown phase", because the merged black hole rings like a struck bell -- a phenomenon that Einstein also predicted.

The scientists were able to measure different frequencies emanating from this rung bell, allowing them to determine the size of the new post-merger black hole.

- Kerr theory vindicated -

This also enabled them to confirm the event aligned with another theory, made by New Zealand mathematician Roy Kerr in 1963.

Kerr predicted that "two black holes with the same mass and spin are mathematically identically," a feature unique to black holes, Maximiliano Isi of Columbia University said in a statement.

Gregorio Carullo of the University of Birmingham said that "given the clarity of the signal produced by GW250114, for the first time we could pick out two 'tones' from the black hole voices and confirm that they behave according to Kerr's prediction."

Scientists are working to find out more about black hole mergers, with several new gravitational wave detectors planned for the coming years -- including one in India.

L.Gallo--INP

London

London

Manchester

Manchester

Glasgow

Glasgow

Dublin

Dublin

Belfast

Belfast

Washington

Washington

Denver

Denver

Atlanta

Atlanta

Dallas

Dallas

Houston Texas

Houston Texas

New Orleans

New Orleans

El Paso

El Paso

Phoenix

Phoenix

Los Angeles

Los Angeles